UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s promise to “get Britain building again” will quickly face a shortage of skilled workers in the very industries he’s hoping will power the turnaround.

UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s promise to “get Britain building again” will quickly face a shortage of skilled workers in the very industries he’s hoping will power the turnaround.

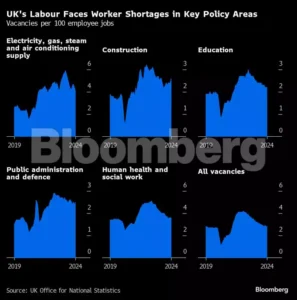

The UK is facing a supply crunch of builders, solar-panel installers and engineers, raising questions about who will carry out Starmer’s mission to radically expand clean power and build 1.5 million homes over the next five years. While the Labour Party has pledged to expand training in key sectors, the scale of the shortages suggest they will slow early efforts to ramp up activity in those sectors.

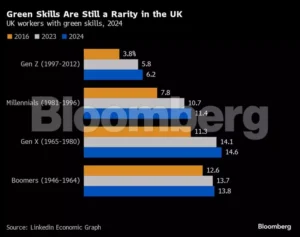

“We welcome the government’s focus on making the UK a clean energy superpower, but the lack of green skills in the UK’s workforce will put this mission at risk,” said Charlotte Eaton, chief people officer at Ovo Energy which employs some 5,000 people across the UK. “The government must urgently map out the regional workforce and identify skills shortages so it can invest where the need is greatest.”

In the run-up to Labour’s landslide election victory, the party had frequently cited skills shortages as evidence of what they said was economic mismanagement by the Conservatives’ during their 14 years in power. Starmer has appointed Jacqui Smith, a former home secretary, as minister for skills, further and higher education. Labour plans to link immigration with training policies and also roll out training programs in sectors like health and social care and construction.

In the run-up to Labour’s landslide election victory, the party had frequently cited skills shortages as evidence of what they said was economic mismanagement by the Conservatives’ during their 14 years in power. Starmer has appointed Jacqui Smith, a former home secretary, as minister for skills, further and higher education. Labour plans to link immigration with training policies and also roll out training programs in sectors like health and social care and construction.

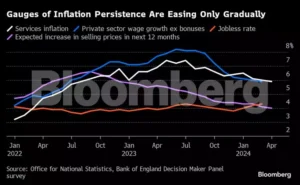

Bank of England policy maker Jonathan Haskel warned that the UK labor market has gotten worse at matching jobseekers to vacancies, meaning that shortages are set to persist even as unemployment picks up. While the UK’s unemployment rate hit the highest level in 2 1/2 years, strong wage growth remains a concern for the BOE ahead of its meeting in August, when it decides whether to reduce interest rates from a 16-year high.

The UK jobs market has shrunk since the pandemic. The number of people in employment has fallen since 2019 after some 800,000 workers dropped out of the labor force mainly due to long-term sickness. Few have returned. Almost a quarter of the UK’s working-age population is economically inactive — out of work and not looking for a job. That’s the most since 2015.

The UK jobs market has shrunk since the pandemic. The number of people in employment has fallen since 2019 after some 800,000 workers dropped out of the labor force mainly due to long-term sickness. Few have returned. Almost a quarter of the UK’s working-age population is economically inactive — out of work and not looking for a job. That’s the most since 2015.

Labour has set a target for the country to produce zero fossil-fuel pollution from electricity by 2030. It’s announced a flurry of plans to achieve it, from reforming planning rules to speed up the construction of clean energy infrastructure to a public company that will co-invest alongside the private sector in wind and solar projects, as well as hydrogen and carbon capture and storage.

This, Labour says, will create 650,000 jobs. But energy bosses worry the UK doesn’t have enough skilled workers to fill them.

Axel Thiemann, chief executive officer of renewable energy producer Sonnedix, is building a solar power plant in Durham that will provide about 100 green jobs once completed next year. He’s having difficulty hiring across a wide range of occupations, from construction personnel and to electricity grid technicians and people who can manage building permit applications.

Sue Duke, head of global public policy at LinkedIn, said the government needs to start delivering large-scale training programs straight away, while businesses have to upskill new joiners and retrain existing workers.

“Workers are coming out of education without any green skills, and they’re not getting exposed to green skilling in those early jobs in their career,” Duke said. “There’s a big awareness gap when it comes to acquiring those skills — only one in five know where to go to get these green skills, then there’s an availability of training challenge as well.”

More Builders Needed

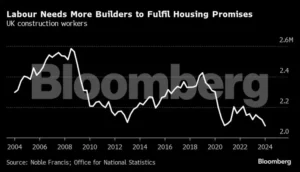

Housing is another area where Labour is high on ambitions and short on workers.

The government vowed to fix Britain’s housing crisis by building about 300,000 homes every year over the next parliament term. That’s target that hasn’t been met by any government over the last 14 years. At most, builders delivered about 250,000 homes a year in recent times.

Even at these subdued levels, the industry has been struggling to get enough builders.

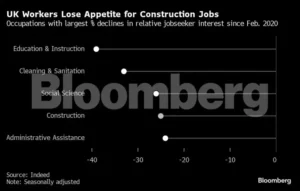

“It’s already the category with the fourth biggest tightening in hiring conditions despite the fact that job postings demand hasn’t been particularly strong,” said Jack Kennedy, economist at Indeed, who warned of looming wage pressures. “If that demand starts to take off, then clearly that that squeeze is only gonna exacerbate.”

The UK’s construction workforce declined about 14% over the last five years to around 2.1 million in the first quarter of 2024. EU workers left after Brexit, while the number of domestic constructors, who make up the bulk of the workforce, fell by 300,000 over the last five years as many older workers retired early. The sector has also lost its appeal to younger staff who tend to drop out of generally low-paid apprenticeships, according to Noble Francis, economics director at the Construction Products Association.

The UK’s construction workforce declined about 14% over the last five years to around 2.1 million in the first quarter of 2024. EU workers left after Brexit, while the number of domestic constructors, who make up the bulk of the workforce, fell by 300,000 over the last five years as many older workers retired early. The sector has also lost its appeal to younger staff who tend to drop out of generally low-paid apprenticeships, according to Noble Francis, economics director at the Construction Products Association.

“New investment in skills and capacity will initially be needed just to get them back to where they were two to three years ago, before the government even thinks of 300,000 net additional homes per year or more,” Francis said.

The government’s net zero target is only exacerbating shortages. In addition to delivering 1.5 million homes, more construction workers are needed to make existing homes more energy efficient, build infrastructure and decarbonize the energy network.

The government’s net zero target is only exacerbating shortages. In addition to delivering 1.5 million homes, more construction workers are needed to make existing homes more energy efficient, build infrastructure and decarbonize the energy network.